Slovenian Punk: A Brief Introduction

I have had a great deal of interest in how and why bands form under extreme political environments, and so when we decided to work on a series of special features focusing on bands active under socialism in the former Yugoslavian Republic, it was the perfect opportunity for me to dig deeper, do more research and look into what has already been written about Slovenian punk; and one article in particular was immensely helpful in understanding the historical events which lead up to the explosion of punk in Slovenia and the rest of Yugoslavia. I am not a historian, and surely history is better documented and passed on by those who made it happen, so that is what we aimed to do, beginning with part one of our ex-Yugo series in MRR #378. The bands featured have some incredible stories, which will surely make other punks around the world revisit their own ideas and ideals, but I figured a short introduction and some background information might help frame the greater political and social picture a bit better. Knowledge is power and we still have so much to learn.

It was 1948. WWII was over. The leader of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, the charismatic bon vivant Tito, had just split from Stalin and the Soviet Union, entering Yugoslavia into the newly formed Non-Aligned Movement. The country’s trade depended heavily on the Soviet Bloc, and with Western politicians “keeping Tito afloat” in hopes of appeasing Yugoslavia into neutrality and weakening the Soviet Bloc, the country plunged into an economic crisis. This was ideal ground for the introduction of a capitalist economy. What followed were two decades of “liberalization” in the ’50s and ’60s (less party involvement in the economic sphere) and a decrease in personal spending due to post-war displeasure, which was in turn met by heavy promotion of consumerism by the party. This lead to an increase in spending, as Slovenian families shrunk to an average of 3.5 members per household. People were buying TVs, record players, washing machines and scooters, many traveling to Trieste, a neighboring Italian city popular for shopping.

An unplanned side effect of this gradual shift towards consumerism meant that, surprise surprise, people pushed aside collectivist social notions for more individualistic consumption-driven ones. As Gregor Tomc says in his enlightening chapter, “A Tale of Two Subcultures, A Comparative Analysis of Hippie and Punk Subcultures in Slovenia“ from the book Remembering Utopia: The Culture of Everyday Life in Socialist Yugoslavia, “Nobody seemed to notice how the emphasis of socialism shifted from creating an alternative to capitalism to entering into a competition with it.” This liberal economic change also brought about a rise in unemployment, which the party dealt with by opening the borders (the known Gastarbeiter), meaning lots of young people could travel abroad and be exposed to Western culture and youth styles. The results of this increased familiarity with the West is what helped the radicalization of the youth movement, and the growth of the hippie and punk movements.

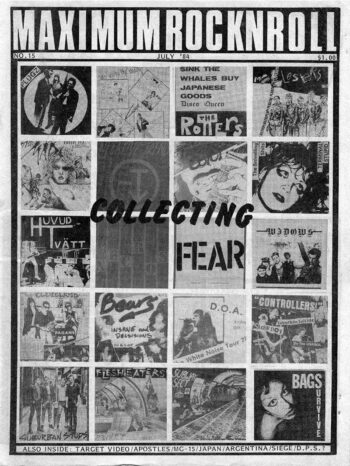

During the ’50s the Yugoslav republic viewed jazz with suspicion, and it was even debated amongst top communist officials, saying that its “unhealthy outgrowths […] have nothing in common either with music or with dance” even though “it can—with its modern expressive means—positively influence the mood of the working man, his cheerfulness.” The only two recording studios were state-run and hard to get into without a record deal, which was contingent on a band’s lyrics, which were subject to the “Committee of Trash,” which basically regulated lyrics and made sure they did not oppose the party. This made access to self-expressed ideas and independent cultural media more difficult. For example, Pankrti recorded their first double single in Italy and any band that did release records made in state-owned studios had to “adjust” their lyrics, giving the art of reading between the lines a new meaning in the context of anti-authoritarian lyrics.

Something to remember, though, is that youth culture in Yugoslavia was developing in a socialist society gradually experiencing the assimilation of capitalism, while still being under the watchful eye of the Party gatekeepers, who were also having to learn how to react to, confine and/or control these new, “decadent” “imported” ideas from the West. This disapproval only made it all the more appealing, of course.

It is hard to imagine a life split in two the way it was for Yugoslavians: on the one hand a public life appropriate for state controlled activities (class-integrated neighborhoods, party-controlled school system, state-run cultural industry) and on the other a private, “spontaneous” life not structured by or around the official state norm (playing in rock bands, joining a commune, or being active in political youth groups). The hippie subculture was an important part of youth culture in 1970s Slovenia, as was the subpolitical student movement, which in some cases resulted in students being more radicalized that the party elite, as expressed in a popular student slogan of the time, “Communism against communism.’” Western student movements were influential in this radicalization, leading Ljubljana University students to protest against dorm rent increases, the Vietnam War, Nixon’s Yugoslav visit, the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, lack of Slovenian minority rights in Italy, and more.

The student youth party was instrumental in the growth and dissemination of youth culture, and so when in the mid-’70s the state forced it to merge with the Alliance of Socialist Youth of Slovenia (ASYS), it left a sort of void which neither the hippie culture (which bored suburban youth) nor the socialist realism movement (the dominant one until then, a mix of traditional working class culture, Soviet block art and Western “progressive” ideas) seemed capable of filling. This was the ideal time for the party to strengthen its influence and, of course, for something new to flourish in the wake of its reaction. Over the next couple of years the punk movement grew tremendously, with more bands surfacing in Ljubljana and all around Slovenia—bands like Pankrti (Bastards), Lublanska Psi (Ljubljana Dogs), Grupa 92 (Group 92), Berlinski Zid (Berlin Wall), KuZle (Bitches), UBR (Uporniki Bez Razloga [Rebels Without a Cause]), III Kategorija (Third Category)—and this just in Slovenia, not to mention the rest of the Yugoslav federation.

One of the things about punk, not only in Slovenia but anywhere where punk has flourished, is that its characteristics are not that of a subculture stemming from the mainstream. Instead, punk springs as a reaction, a counterculture. Of course this meant that, even if the societal background in Slovenia was not necessarily adverse to youth cultures (as Slovenia was one of the most developed states in the Yugoslav federation) the system, which was losing control over media during the ’70s and ’80s thanks to new media technologies, viewed them with suspicion, even confusion. So, once the party finally declared its disapproval of punk, this opened the way for increased suppression from the state police. A number of incidents occurred, but perhaps the most well-known was the “Nazi punk affair,” when a populist newspaper wrongfully assumed three Ljubljana punks, who were sporting “Nazi Punks Fuck Off” pins with swastikas crossed out, to be members of the Nazi party. This resulted in their arrest under the charges of secretly trying to start their own IV Reich(!). It was clear that punk was no longer considered to be just a symbolic threat.

The student movement, despite having merged with the Alliance of Socialist Youth of Slovenia (ASYS), was still a major contributing factor to the evolution of punk. The elderly party elite figured it no longer played a leading role in the political landscape and dialogue, since it was now under party regulation. However, they underestimated the student movement power and, with the help of people like P. Mlakar (a poet, philosopher, artist, book editor and more), Igor Vidmar (a radio DJ, concert promoter, political activist and more) and other members of the student movement, they supported punk by playing punk bands on the radio, promoting their shows, publishing their comics and recording their records. If Marcuse’s “repressive tolerance” is where capitalism and totalitarianism meet, then Slovene punks were having to balance the thin line between the two, stemming from the former and growing into the later. Such a system clash is ideal for the eruption of youth movements, especially one as vivid and forceful as punk. Much like when two tectonic plates collide and mountains are formed, Slovenian punk rose, growing past the police interrogations, the arrests, the censorship, even Tito’s death. It would not be wrong to say that the punk movement in Yugoslavia helped society further open up to the concept of revolution, and this is perhaps where its strongest appeal lies: in the manifestation that, yes, punk can be more than just music, concerts and records; that, in fact, punk was and can still be a powerful force of social change. In his introduction to an interview with another Yugoslavian band Pekinska Patka, from Serbia, Spencer Rangitsch says that they “didn’t just push the envelope’ of what was deemed socially and politically acceptable, they also broke boundaries in radical ways which helped create new spaces and possibilities for a youth subculture to thrive.” And that sounds pretty fucking punk to me.

These is much to be said about this unique time and place, and my short introduction is by no means a comprehensive deposition of all the facts—one could fill books and books and still have more to say. This was, however, the most relevant information I found, in large thanks to the aforementioned paper by Gregor Tomc. There is probably less written about punk in Yugoslavia during the Yugoslav wars that followed Tito’s death, but that is not to say that it did not exist. The idea behind this Ex-Yugo Special is to learn more about how and why punk erupted in Yugoslavia under socialism, and to shed more light onto how punk survives during and after wartime. Hopefully in the process we can broaden our horizon of punk history, helping us better frame our own perceptions of it. One of the most important characteristics of punk, for me, is the realization that, since we chose to create, and thus define the culture we engage in and the life we lead, then it is also up to us to preserve and document it. I am honoured to be able to offer these pages to some of the unsung progressives of the first wave of punk, and in doing so express my admiration for their contributions to it. Ladies and germs, Slovenia.

I have put together a shortlist of some of my favourite Slovenian punk songs. Not a comprehensive list by any stretch, as there are many bands missing, but here you go anyway. In no particular order:

O! Kult “Za Ljudi” from their Mladi Imajo Moc EP, which translates to “For the People,” declaring, “Freedom is a scam!” You can read more about O! Kult here.

Quo Massacre “V OÄeh” from their Kje Je Odgovor! LP. The title means “In the Eyes” a track that stuck with me the second I heard it, and which is a prime example of how, even if one cannot understand the lyrics, the music speaks volumes.

KuZle “Vahid” from their Archived LP, which talks about a Serb boy being in love with a Slovenian girl, but her father disapproving of the relationship. “Vahid, Vahid where are you going, you know you cannot go there / Vahid, Vahid go home, forget about her address” is the moving translation I get online for the lyrics.

Indust-Bag “Ti Si Stroj” from their Zavrzena Mladost LP; the song title translates to “you are a machine,” while their record title means rejected youth.

Grupa 92 “Od Å estih do Dveh” from their Od Å estih do Dveh/Tujci 45, this song is called “6 to 2″ and the lyrics talk about the monotony of the work schedule.

UBR “UBR” from their split with Croatian band Patareni. A “no future” manifesto for rebels without a cause, clocking in at exactly one minute. UBR were definitely heavier than most of their peers, breaking through into hardcore.

Tožibabe “Dejuže” from their EP of the same name. They were the only known all-girl hardcore punk band in Slovenia at that time and this track is a phenomenal, unrepeatable classic. Trailblazers and an inspiration for womyn everywhere.

Å und “Komisija za Å und” from the epic Lepo Je… compilation. “Lepo Je…” in Slovenian means “It Is Nice…” and the subtitle to this comp is “…V NaÅ¡i Domovini Biti Mlad” (“…In Our Country to Be Young”) epitomizing the irony felt by punks under the socialist regime.

III. Kategorija “Agresor” Heavier than their peers, Third Category forged a hardcore sound on the way to being metal (check out those solos!) and in some cases even noise not music before that was a thing. This band has also recently been re-released, and this song appeared on the seminal compilation Hard-Core Ljubljana.

Stay tuned for Part II of our special feature on Ex-Yugoslavian punk: Croatia.