Threat by Example. An interview with Martin Sprouse by Martin Sorrondeguy.

This originally ran in MRR #291/Aug ’07. The 25th Anniversary Issue which you can order here

All photos courtesy of Martin Sprouse.

OK, Martin, why don’t you start off by talking a little about yourself—tell me who you are and how you first got into punk.

My very first exposure to punk was in 1977. My next-door neighbor was an art student, and he became punk overnight—like crazy Sid Vicious punk—overnight. I had just seen something about punk on the news, and all of a sudden one day he shows up—he’s got a punk rock girlfriend, a Sid Vicious look head-to-toe, messy hair and spiked jacket and harnesses and boots—the whole Vivenne Westwood type of thing. They looked amazing, like the most outrageous thing in the world. He played some music for me; I didn’t understand it at all. I was just a skater kid, and I was just thinking, “That is the most fucked up thing I’ve ever seen.” But it was also cool, because he was the nicest guy in the world. This had to be ’77. So that was my first exposure, and I had a positive impression of it, but I didn’t understand it at all. It was just too crazy. And I was probably just a little too young to get into it, you know? Later on, when hardcore came out in the early ’80s, it all made sense. It was kind of connected through skateboarding. Punk and hardcore kind of fused for me, being young and in Southern California where everything was happening. It was like, “This is it!”

Where did you grow up?

San Diego.

You got into hardcore when hardcore pretty much started, so what was your first show? What was that experience like?

It was a local San Diego show, just San Diego punk bands.

Do you remember who played?

No. I remember seeing Black Flag early on, and that was life-changing. It was crazy. Southern California was really violent at the time, but we were young, so it all kind of made sense, but at the same time it was really sketched-out, you know? So it had this crazy energy, really exciting, really underground, really small, really young, youthful, violent. Rebellious in all the right ways. You know, when you get older, you over-think everything, everything’s theory and process. This was full-on energy, Southern California hardcore punk rock. It was scary too, but in a good way. It just defined you immediately. Everyone that you were friends with didn’t like you anymore, you know, because you were a “punk rock faggot.” I think that was my name for most of the rest of high school.

When did you start Leading Edge zine—how did that come about?

A couple of us who grew up together, we all got into punk and hardcore about the same time. It just sort of happened; it was very spontaneous. We weren’t really the fucked-up kinda kids, we were all skater kids. We didn’t really become the stereotypical early-’80s punk rock asshole guys. We immediately became friends with people that put on the shows, we started reading the little underground xeroxed fanzines, we became friends with the bands. It became a natural extension for us to do something. We’d go to LA and get these fanzines from all over the place and that’s how you’d learn about everything. So immediately, it was like, “We should do it,” once we started going to LA. We started Leading Edge in like ’82 or ’83. It was a while after we’d seen some shows. The first issue must have come out the summer of ’83.

Why did you do it?

Just to do our own thing. It was obvious to us…’cause San Diego had the military there, so a lot of punk guys were in the military, it had the violence, a lot of drugs, a lot of fuck-ups, y’know? It just had a bad reputation. There were a lot of fights in LA, but there were twice as many fights in San Diego. It just sucked. Out natural extinct was not to be a part of that. We didn’t want to be the stereotypical SD “Self-Destruct,” “Slow Death,” fight-starting, maybe shaved-head, junkie thug, beating everybody up. None of that had anything to do with us—but we liked the energy of the hardcore scene. There were also a lot of young hardcore bands that weren’t part of that; younger bands that weren’t doing stupid shit, but still playing really fucking great hardcore. They kind of identified with us and vice versa, and we started a fanzine that would represent that, while at the same time respect all the other stuff that was going on. I wasn’t just focused on skate punk or straight edge punk or positive punk, we were covering bands from all over.

How did people at that time take to the fanzine?

Some took well to it, others did not. We almost got out asses kicked several times. It was fucking insane. People from the local record store, Off the Record, and people putting on the shows were really supportive of it. The first issue was just a funny little xeroxed thing, it looked like every other punk/hardcore zine at the time, but they were really supportive of us. We sold it at shows, and people understood what we were trying to do. We had lots of artwork and photos in it. It had a heavy graphic look to it. Then there were other people, like these other fucking thug-type guys, who thought we were taking over the scene. The old San Diego guard was kinda gross. There were a lot of good people doing things but it was just fucking drugs and lameness, you know? Mostly drug people who liked hardcore.

Who else was involved?

I started it with this guy named Pat Weakland—he was a kid I grew up with. Then this other guy came down in the summer of ’83, Jason Traeger. Jason was the guy who did all the drawings and stuff that everybody saw. If you remember, we had a lot of crazy-ass drawings. He was an amazing artist. He lives in Portland now. For a time, it was the three of us, then Pat left and it became me and Jason.

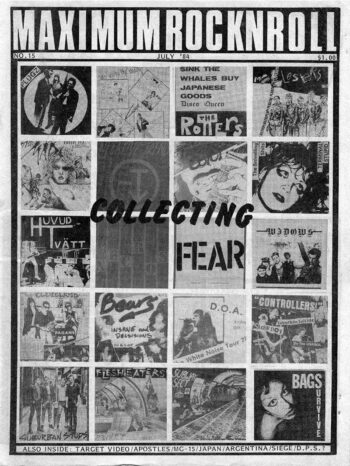

When did you first hear of MRR?

Right when the record came out. The first compilation.

Not So Quiet…?

Yeah, with the first issue. We were in LA and I remember Pat and I were in a record store and we were like, “It came out!” He knew about it and when it came out we listened to it and it was like…it was really crazy ’cause it was so different than what was going on in Southern California. San Francisco had a whole different feel. It was such a mythology type of thing ’cause you know you didn’t really find out immediately how things were. You kinda made up a lot of things in your head, read things in magazines, put the pieces together. In San Francisco things were a little bit older, way more political, way more serious. Nonetheless, when the record came out we found out the first issue of the fanzine was in there, then Off the Record started carrying the next issue and I remember picking it up off the counter and going “Fuck, this is amazing!” This thick, newsprint zine. I think one article had a photo of someone laying on the ground in front of the Bechtel building. That was the first issue that came out in the record stores. I remember I held it up, thinking “A punk rock political fanzine this thick!” It felt like something had just been taken to a whole different level. It’s punk, it’s hardcore, it’s serious, and it’s thick, and the cover image was so bad-ass and I was just like “Hmm, makes sense.” It was great and it was always right there from the very beginning. I think we immediately began contacting them and doing scene reports for San Diego and stuff.

How did you actually get more involved with MRR after you started doing scene reports?

I came up for a visit with Bones, he was the singer for CIA from Connecticut. He came out and visited me in San Diego, and me, him, and some other people, my friend Jeff and his girlfriend, drove up here one summer to the old Maximum house and there was an earthquake and that’s when I first met Tim. I guess I had already been doing scene reports, but that’s when I first met him. It was that first little summer road-trip that I stayed up here for a bit and me and Tim hit it off. I think he had called me on the phone before that and asked me to write a San Diego scene report so we had had contact before that.

So, how did it happen that you moved up here and started working for MRR?

So, how did it happen that you moved up here and started working for MRR?

We used to come up here and visit all the time at that point and then—and this is actually a really crazy piece of MRR history—but me and Tim were getting along, and me and Jason would come up here, and Bessie who used to play in The Wrecks, who are on the first Maximum comp—she was from Reno—she would come up here and all of us would hang out. She was hanging out with the 7 Seconds guys ’cause they were always in San Francisco and we knew Bessie. It was just a tight little hardcore community. We were all over the West Coast and we all kind of just met each other all over the place. I guess we had met Bessie when she was working at BYO. Anyways, all of us were in the Bay Area one time and Tim made this proposal to me, Jason, and Bessie, asking us to take over the magazine ’cause his long-term plan was to open a club. That was the very beginnings of what eventually became Gilman.

What year was this?

That was the summer of ’84. It was supposed to be me, Jason Traeger, and Bessie, and we were gonna take over Maximum together to allow Tim to go find a place to open up this “grand scheme” club run by the punks for the punks.

What was your reaction to that?

I guess I kind of knew it was coming. It just seemed great. I instantly was in. I didn’t even hesitate. It was really weird ’cause when you’re young, you just kind of go for things, whereas now I’d contemplate that decision for a long time. I’ve actually been thinking about that decision a lot in my life lately. That was a life-changing decision. It was just a split-second teenage decision but it was a nice thing. I liked that Maximum was a group effort and all the people who worked on it were always really inspiring. Every single shitworker was a total character and an amazing person on their own. It didn’t matter if they just did a layout for one day. A lot of those people are still doing it, you know? Anyway, it was a pretty amazing offer. I don’t think Jason and Bessie were as into it as I was, and ultimately they both dropped out for various reasons.

So they didn’t come out as well?

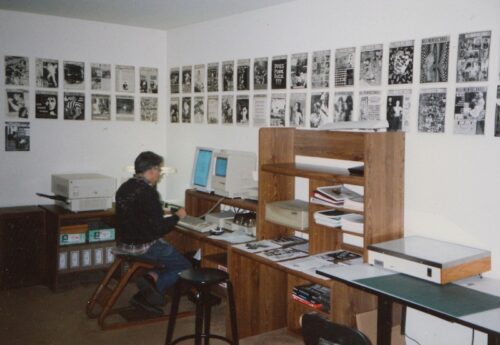

No, they both dropped out of the deal. They decided not to come so it was just me moving up, finally, in the late summer of ’85. Tim was moving the zine from Berkeley to San Francisco, so in September we got that house on Clipper Street and we all moved in together. The idea now was that me and Tim would kinda coordinate Maximum and the club thing would just start happening also. It was still a plan but it wasn’t like he would leave the magazine a hundred percent and it wasn’t like I would take over the magazine. It was kind of like I would help out on the majority of the work and allow him to go find this club, which happened pretty quickly after I moved up here. Also, the magazine changed really quickly after I moved up there, ’cause in the beginning the magazine used to be run by a large group of shitworkers, much like it is now, but there were never really coordinators like there are now. Tim Yo was there, but a lot of people would come in here and there and volunteer. They’d have these important workdays on Sunday, which was a pretty amazing thing. Then when I came up there, me being a workaholic I couldn’t wait around, and me being a control freak, I wanted to change the whole magazine instantly.

Would Tim pull back on things?

Would Tim pull back on things?

Yeah. At the same time Tim was pretty…He had his own controlling side and we’d butt heads, but at the same time, his take on the magazine or any project he worked on was that the more work you do the more voice you get. He saw my enthusiasm so I was able to do the work. He let me make mistakes and would actually back me up, and like I said, we actually butted heads on certain things but it kinda all worked out. Tim’s joke was that I fired the staff. I didn’t fire anybody, it was just that I was doing a lot of the work or me and Tim did a lot of the work together and the Sunday work parties kind of fell apart and things changed and it became more of an individual thing kind of like how it is now. People would come in on certain days like, we’d need help on typing or we’d need this done or we’d need that done. It was still very much a community or volunteer thing though; all of us were still volunteers no matter how much work you did, just like it is now. The structure is just different.

So these Sunday work parties, people would just show up on a Sunday and everybody’d just go all-out for a couple hours putting together and laying out the next issue?

Yeah. Then they’d buy food and snacks and eat. That’s when I first met Paul Curran. He used to come to those Sunday meetings at the old house in Berkeley. A lot of the old people as well. Then it was transferred to the Clipper Street house and it disappeared pretty quickly after that.

That’s interesting, ’cause we do “new issue days” on Sundays [when every copy of the new issue is packed up and shipped out to distributors and subscribers]. We do the whole food thing and people help stuff envelopes and all that, but I couldn’t imagine doing the whole zine like that.

It was also a lot smaller then. Tim would have layouts ready for people or typing ready for people. He’d spend the week getting ready for the Sunday thing and just jam on it. It was pretty interesting. Then when both of us were just working so much it didn’t happen that way cause me and Tim were definitely workaholics. Again, we didn’t do all the work. Shitworkers, the staff of Maximum was always there. They really brought that whole thing together.

What were some of things about MRR that drew you to it that you liked so much about it?

It was global. It was one of the first zines that made you realize that punk was happening on a global level. Very few magazines do that, even today, and that’s pretty amazing. We were doing that before anybody else. Where else were you gonna hear about mohawk punks in Brazil in 1983? Nowhere. Then you find it and then you start hearing music, and Jeff Bale was bringing in all this crazy stuff and you first got to hear about Finnish punk through that. The global aspect of it was amazing. The political side of it was amazing. They would do an article about the government or Bechtel or something like that, or something like the draft. I thought that was great. Also, just the resources that the magazine had—they were able to put out that record. All the bands went there, all the records went there. You could find out what’s going on. Also I think Tim had long-term plans. He was always thinking twenty steps ahead of people. It was kind of exciting being involved in something like that. You knew it wasn’t gonna be some sort of stagnant, “Yeah whatever, let’s just do this” thing. It was dynamic. It was doing something but it was all in the punk world. That was the stuff that drew me there.

How did some of the magazine’s policies come about?

It had a lot to do with Tim Yo; a lot of that stuff was already in place before me. It wasn’t really like some sort of ten-point program or some sort of manifesto—there was nothing like that. It was kind of simple and common-sense, much like how the magazine now runs—not a set of rules but kind of a common understanding. The volunteer thing wasn’t very complicated to understand—you volunteer at this magazine, you get benefits. You get free magazines, you get some records, some exposure, but the money is used for other things. If you don’t wanna volunteer it’s alright, but the more volunteering you do the more voice you get in the magazine. You can kind of help change the magazine or guide it in a certain way, knowing it’s not gonna go to one extreme or the other, but you can start becoming a part of it. It’s very open. All of that stuff is kind of given and had been decided beforehand but always kind of made sense. Much like how Gilman still kind of follows by the same rules as when it opened. That’s one of the most beautiful things in the world. This super-rebellious, super-independent, super-fuck-you to everybody else thing, and being very productive at the same time. Not giving a fuck, not reacting to anything, doing your own little thing and going a hundred miles an hour. Some of the more funny policies like what is punk and what records would get reviewed and what ads would run, all that…that came later. But the whole culture and all that, if that’s what you were getting at, all of that was already established and understood.

Yeah, all of that was established before you got here, but how did some of the other stuff you mentioned come about?

It was pretty organic and obviously it changed as time went on and the situation demanded it. When I came to the magazine there was no major label punk—a lot of the ’77 bands that had signed to major labels were already gone, so it wasn’t an issue. It came up later in the ’80s when some of the bands started doing things. That became…it was just that we felt that major label corporations and punk just didn’t mix. I remember when Hüsker Dü put out New Day Rising. The guy behind the counter at the local record store said, “We’re selling Hüsker Dü records to college kids. This is college rock.” That’s the first time I ever heard that phrase. College rock? Hüsker Dü? I couldn’t understand straight kids listening to Hüsker Dü, and there it was, the beginning of the end [laughs]. Then when Hüsker Dü signed to Warner—that was probably the big thing. Tim called Bob [Mould] and had him do an article or column about it. So, yeah, I think that was the first time the major label thing started coming up. I think it was somewhat of a natural policy, but something like the magazine’s re-definition of what was and was not punk—that would definitely change as punk music would change. When I came up here in ’85 a lot of the hardcore from the early ’80s was gone and people were trying different things. The magazine would have to deal with a situation like—a punk person would put out a country album and they’d be bummed out that we didn’t review their country album just because a punk rock person did it. The whole idea was very simple, it’s a punk rock magazine, we’re gonna review the things that we cover in the magazine, not anything else. Just because something’s DIY doesn’t mean it gets reviewed in a punk magazine. It’s common sense stuff like that and we stuck to it. But there was always enough punk that was falling under our definition or our focus or our scope or our interest already, there was millions of records coming in every day. So it didn’t really matter that these other bands were trying to do major label stuff or do different music or change things around. There was always a million other bands that we liked that were there.

Was there a feeling of “well, fuck you” from people you once supported and then didn’t for whatever reason? Was there resentment toward you, because maybe they felt you turned their back on them?

Yeah. I’m sure people didn’t agree with our definition of punk. They thought punk should be broad, and we shouldn’t exclude certain bands. I’m sure that argument happened long before Hüsker Dü went to a major. The perfect example is the blowout with Jello and Alternative Tentacles. Jello did this split album with this alternative, smart-ass county guy from San Diego. We refused the ad, because it was a record that we wouldn’t review, so why would we run an ad for it? We only run ads for stuff we review. That was the beginning of one of a million blowouts with Jello and AT. Not to just focus on Jello, I really don’t want to get into that, but it was an example of him not understanding what we were doing. Him feeling like we were turning our back on him, that we should be open to everything that was punk-related, DIY. Jello had and still has very eccentric taste in music, and supports tons of things in lots of different genres, where Maximum is very focused. Some people don’t have the same definition as us, but they keep putting out records, and they keep doing their own music, and Maximum keeps on doing our own thing. It didn’t stop us at all.

But what about within the magazine itself—was there any kind of head-butting within the magazine because of all this type of thing?

All the time. Every week. It’s a big staff. A lot of people like a lot of different conceptions of punk. Just as an example, people butted heads with Bruce Roehrs ’cause of some the stupid shit he likes. The band thing, the definition of punk, people will always butt heads on that. It has been there since the beginning of Maximum, it will always be going on ’til the end of Maximum. Some things were definitely instigated by Tim. I saw Tim purge his record collection twice. He re-defined what punk was to him. He listened to every single record in his record collection—the famous Tim Yo dropping the needle thing and if it sounded like crap he’d get rid of it.

When we were talking before, you said Tim was 20 steps ahead of everybody in the way he thought, that his process was different than a lot of other people. Where was he trying to get?

I meant it more like—he was a strategy guy, like him playing Risk every Wednesday. Everything he had touched or was doing was structured but needed to go to some other avenue. It wasn’t like punk rock domination, it wasn’t about getting money or power, but it had to do with living by example. Like, start an independent mail-order, start a club, start a magazine, start a radio show, and do it all with the same ethics. It wasn’t like a master plan, but more like logical steps: radio show, records, magazine, special issues, club, record store, distro, and helping community projects out. It was just a very logical step, and he was definitely thinking 20 steps ahead; he understood where the next thing to go and he jumped right onto it.

I’ve always known Maximum Rocknroll as a zine and Tim being a person who helped a lot of people out. Can you talk about a bit about that, ’cuz a lot of people never saw how much Maximum was helping other people and projects out.

It’d always be at the end of the year when the magazine was making lots of money, we’d give the money away. And a lot of times that’s where people who volunteered at the magazine—it’s not like a paycheck, but it’s like here, we got an extra $10,000 at the end of the year, let’s give a bonus to all the shitworkers on the magazine, and if we had more money than that let’s go a little further. Let’s give some to everyone that did a scene report or an interview or anyone that helped out with distribution. No one expected it at the end of the year, the amount differed every year, sometimes we went really far with it and gave money to random fanzines that we liked or thought were doing good things. Y’know, send ’em some money, like $100. It was just about spreading the wealth within the community. That was part of the amazing thing about the volunteer aspect: nobody was taking a wage, so all costs were covered and there was a lot of money left over to use. That’s how Gilman started, with money from Maximum.

Did you feel like, once you started working here, and after you had been here a while, it changed your perspective of punk?

Well, obviously, yeah. I moved here when I was 19. I stopped working on the magazine in, ’99, 2000 maybe? I grew with it. I’m sure it would have been different if I had stayed in Southern California. Maximum Rocknroll was like my school. I never went to college. I learned through experience, and I got to do a lot of things that other people didn’t by being involved with all of these projects. Being around all these people, and meeting all these international people who used to come and visit the house and the magazine was amazing. And also be involved in these great community projects, helping start those things was a pretty amazing thing as well—it shaped me. I don’t know if it really changed my perception of punk. It definitely matured it, and educated me.

How has that changed after you left the magazine?

Personally, I stayed on at MRR about a year after Tim died—not just me but Timojhen Mark, who was a big part of the magazine, and a few others. People who would stay here and—not watchdog, because the magazine was pretty much operating on its own—but be there and be sure things were going the way it was. It was set up already to do that, the people who were doing the work were really pulling it together. After that, it really started when Tim died. It was time for me to go. Me and Tim worked really well together. His dying was a life-changing event. The new kids were coming up, they had the same ethics as we did for the magazine, but they understood all these new versions of punk. It was great. It felt like they should be the ones covering it. My taste in music had changed a little bit. I still loved punk, but I didn’t really like some of the new stuff that was coming out. These people did, and I understood and respected that. It’s great that they were there and taking it over. Maximum has a great sense of community. Obviously I’m still friends with some of these people, but I miss that family. I don’t have it now. I can still see people all the time, but everyone’s getting older and growing up, it’s weird. But it’s great that I still run into old Maximum people, punk people, quality people. Just seeing Bruce now, crazy Bruce…

I’m going to jump around a little bit. To this day, Maximum Rocknroll is very controversial to certain people, in a lot of different punk circles. Why? What is it that gets under some people’s skin?

I think early on, people thought it was a power struggle, with us trying to take over things. But really, it wasn’t. Take over? It never was. It was a myth of a thing bigger than it really was, more powerful than it really was. I think people hate Maximum because it calls people on their shit. Be it skinheads, fuckin’ stupid, dumbass, really bad punk rock, shitty labels… Maximum called people on their shit and stirred up shit, you know? I think that was kind of a Tim Yo thing, too, through the radio show. Calling people on their shit, and people hated that. A lot of times, people want to listen to punk rock music for it just to be punk rock music. That’s never gonna be part of Maximum. Maximum’s always gonna be the message, the community, the music—all that together. Another thing that people have this wrong idea about—Maximum’s really a music magazine. Tim Yo loved punk rock music more than anything. He had his politics, his feisty side, his troublemaker side, his own personal politics, but he just loved fuckin’ punk rock music more than anything. You’d see that inherent enthusiasm of it, like, him playing air guitar every time; at 50 years old and he’s playing air guitar to some new young kid punk rock record, and loving it. He just loves fuckin’ music. Maximum Rocknroll is a music magazine. People forget that.

What were some of your favorite things about MRR?

I like the photo issues. The first photo issue we did with Murray Bowles, that was pretty amazing. Murray is an amazing guy. He still goes to shows now! Here is another super-passionate community guy, he loves the music, goes to every fucking show, takes amazing photographs all the time, gives ’em away to kids, knew everybody’s name, went to house party shows… That was a pretty amazing thing, working with Murray. And Murray’s such a quiet, humble guy, and he did this crazy, beautiful photo zine. Then we did the international one after that…

Welcome to Cruise Country…

Those were really fun. Of course, the Gilman thing was amazing. That happened pretty early on after moving up here. Being part of Gilman for those first two years, seeing those bands, that was another—and I hate to use such a corny fuckin’ Berkeley word like “organic”—but that was just something that happened very naturally and beautifully. That was a great thing that happened there, and it’s still happening now. That’s where Threat By Example came out of—a counter-culture that had nothing to do with normal business, normal ways, anything. It’s still there and staying around longer than anything else.

That’s funny, because when you talk about it, it almost seems like the zine was secondary, that the experience was primary.

Definitely the zine was a key part, because we worked on it every single day, and I was definitely a zine person. I’d rather work on a zine than help with punk shows. I don’t wanna give the wrong impression. I was there at Gilman, but I’d rather be home doing cover layout or something, so that was definitely my focus, all things printed. One thing that drove me crazy was those super shitty, badly drawn headers that used to be the scene report headers, drawn in 1983 by someone with a ballpoint pen. It was so fuckin’ ugly. That shit drove me crazy, and Tim goes, “[in a squawking, mocking tone] I love them, those are great. That’s punk! Throw it in there.” And my whole thing was, punk wasn’t sloppy, didn’t have to be sloppy. It wasn’t trying to make punk clean, but I didn’t think punk had to be drawn with a ballpoint pen. That had its place, but at the same time you could do something graphically interesting, too. Graphics was more my thing. I still liked going to shows, but I was way more a behind-the-scenes kind of guy. Anyway, the magazine had started before I’d even come here, so it was a community thing that I put my own voice in. It was always a by-product of a lot of people, a lot of different voices. It was great and rewarding every month, but we still had our monthly parties when the new issue came out, everybody helped put it out. It helped stir up shit; it was amazing. We started putting the covers on the wall, and we’d just see another issue done, and we were onto some other issue. Time went by really fast, because that’s all we did. Somehow I lost…You how people do drugs, they lose fifteen, twenty years of their life? I did fanzines. Maximum, Gilman, somehow I lost fifteen, twenty years of my life. I don’t do drugs, but I don’t know what happened. It was a really strange thing. All of a sudden I was like, “I’m old?”

OK, you brought up before something that was a segue into the book Threat By Example. How many books did you release?

Uh, Pressure Drop Press released five printed projects.

Were they all your books or were they other people’s?

Three other people’s books and two of mine. Threat By Example came out of me wanting to do my own thing cuz Maximum was never gonna totally be my magazine. I could definitely have my input on it graphically, or content-wise, but it would always be a group thing and it would never fulfill me 100 percent. I think in ’88 after being in San Francisco for a while I decided to do this book, and wrote out a list of people who had influenced me that were involved in the punk rock scene and had them just talk about what inspired them, what made them who they were and why they kept going. And basically why their life is a “threat by example.” I stole that line from Noam Chomsky. They are showing how its done and anybody can replicate their example, and that’s a threat, as subtle as it is. Some people in the book were famous in the punk scene, some people were just more my friends. It was taking a fanzine idea and putting it in book form. It came out in ’89. I didn’t interview anybody; I made people write their own things, which is a really insane, weird idea. I don’t know why I did that. I guess I wanted it in their own words, but it wasn’t really the best approach. It was really hard to get these people to do things. But all these people were writers, so they could do it. So it wasn’t interviews, it was artwork and people writing their own life stories.

You said, after Tim passed, there was a point when you decided it was time to move on. Did you feel, with his death, that there was a disconnect for you?

With Maximum? Not in a bitter way. I felt really secure, like we’d put a lot of work in before he died to make sure it would keep going on. We’d selected some people that would do it. Some of those people worked out, some didn’t. We went through this long mode of trying to figure out if we would keep it going. I remember voting that we should close Maximum down after Tim died. Which is funny, because Maximum has obviously kept on going, and it’s doing great. But there was a time when I was voting because I thought, “Ah, it’s not gonna happen.” We couldn’t find anybody, or somehow I just thought we should close down. But there were enough people who wanted to keep it going, and not just to replicate something we had done in the past. Not just be true to Tim. The most important thing was to keep a new voice going that was still based on the same groundwork as Maximum; that was the most important thing. If anybody just mimics what we’ve done in the past, it’s just gonna come off as cult-like and corny, and it’s not gonna hold up. Incidentally, after two years of Gilman, I also voted to close Gilman down too. [laughter] To get back to your question—I came up here to work with Tim on the magazine. But me and Tim were really good friends, so our relationship is a deeply personal thing. That was a super crazy thing, his death. As was being here—it was all happening, and I was watching the whole thing go down. I was right there. It’s not that I was grieving so much so that I couldn’t be here. There was new people here, the vote was done, it was really strong, the foundation was here, so after a year, watching it happen, I was able to walk away. It’s been painful but at the same time it was time for new people to take care of it. I never regretted the decision. Like I said, that was the most life-changing thing that’s ever happened to me, dealing with Tim’s death like that.

Can you believe this is the 25th anniversary issue of MRR?

Well, coming from someone who at the time felt it should have died when Tim did, yeah it is weird. And I think it’s great. If it didn’t have a credible 25 years then I would think it was really bad. It is weird ’cuz when you are doing it you never think of what its longevity is going to be. I never thought about that, I just did it day-to-day. Then all of a sudden 15 years have gone by and I’m like, wow! You still keep going. 25 years ago doesn’t seem that long ago, to me. I remember all these events vividly. It seems just like yesterday, when it is really a long time ago. I don’t know if I ever grew up. I don’t think I am living in the past. I don’t cling onto it but it’s nice that it’s not such a distant memory. I am glad Maximum is still around and that it didn’t close when I wanted it to. I am proud of it.

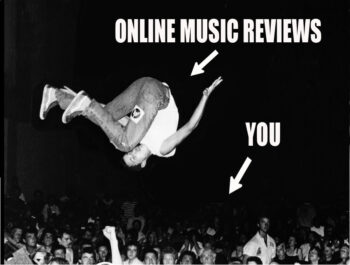

Do you still feel punk and MRR are still viable, today?

Yes. Why wouldn’t it be? Punk’s still alive. I get more embarrassed when…what makes it viable, but makes it kind of gross at the same time, is when people repeat history. That totally bites me. And of course now that’s happening more than ever, ’cause punk bands never fuckin’ break up. So you see 50-year old guys playing songs from 30 years ago. That’s one of the most embarrassing aspects of punk, to me. Or doing reunion shows, whatever. What I like about punk is that there’s always new generations rebelling against the older generations. They might like the older stuff, but they’re making their own new version of it. It’s not like re-inventing the wheel—they’re not bringing xylophones and saying, “This is punk now.” It’s the same, basic, three-chord stuff, but it’s their own version of it that comes out naturally. It’s happening all over the world, and it’s great. When people just rehash old stuff, that’s the fuckin’ worst thing in the world. If punk was just a bunch of old fuckers singing about the old days, then it’s dead. When there’s no new ideas, it’s dead. When there’s no new fight, it’s dead. If it sounds like shit, or it doesn’t make you rock, it’s dead. When you see young kids—and they don’t even have to be young—but new music coming out that sounds different, is different, and still making trouble and calling assholes out on their shit, it’s beautiful. That will never get old, ever. And the magazines that represent that, or the websites, or whatever medium, it doesn’t matter, all the content that Maximum has to offer, or that view, covering that stuff, it never gets old, it never loses its importance.